Mes Aynak, AFGHANISTAN

A VALUABLE COPPER DEPOSIT

AN IRREPLACEABLE ARCHEOLOGICAL SITE

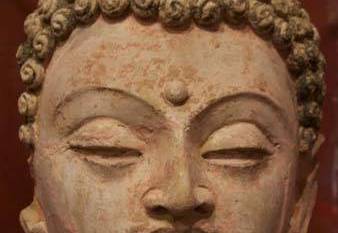

Mes Aynak means “little copper mine.” Maybe it was little once. With today’s technology and mapping, it happens to be one of the world’s largest unexploited copper deposits. But also: one of Central Asia’s most important archaeological sites.

About

Mes Aynak is a 5000-year old Buddhist city, one of the most important archeological finds in all of Central Asia. A sprawling complex of stupas, temples, residential areas, markets and a fortress, it sits on top of even older remains of ancient mining and trading villages.

Problem

An enormous copper deposit is also located here. When we first got involved, the stated plan was to physically remove as many items and structures as was possible in a hurried salvage operation, put them in a museum, and sacrifice the rest of the city.

Location

Mes Aynak is in Afghanistan’s Logar Province, 40km outside of Kabul, a way-station on the former Silk Road.

Solution

For seven long years, ARCH begged, pleaded and argued for the salvage archaeology to cease until there was an actual reason for it.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

Share our conference report and other ARCH publications on the issue with your friends and colleagues. Post on social media, on Twitter, on your blogs. Start a discussion based on real facts on the ground. Let people know that there is a solution.

We still have a chance to get things right. Calling all bloggers, all Buddhists, all mining experts, all journalists – help us get the word out.

Background & More Information

Historians believe that mining has been going on here for millennia. In the days before explosives, chemical extraction and machines, mining was a gentler enterprise. Thus, a village and then a town and ultimately a vast, prosperous city grew up around the mine. The high point was during Afghanistan’s Buddhist era, but there are pre-Buddhist remains below that city. In short, this place is a treasure trove from a scientific point of view, promising unique insights into the early history of mining, a window into a period when Afghanistan was a “technology leader” for the extraction and working of metals, and into a premier site along the Silk Road. But it also holds enormous economic promise for future tourism. Easily accessible from Kabul, this could be Afghanistan’s equivalent of Pompeii, a city where visitors can wander among temples, stupas, municipal buildings, forts and marketplaces.

At this moment, Afghanistan is in dire economic need. The possibility of near-term income from a mining contract is understandably more appealing than the prospect of future gains from science and tourism. We get that. Our problem is that no serious effort was undertaken to see whether this truly had to be a zero-sum game. Was there a way to do the mining, and still preserve a good portion of the site?

And what we could not understand at all, was how such far-reaching decisions were being made without proper information. There was no mining survey. There was no detailed map of the archaeological site. Without those two things, you couldn’t even really determine what was or was not possible. And, there was no Environmental Impact Study, even though Mes Aynak sits atop the country’s main aquifer, and copper mining carries special risks, and endangering that water supply would have consequences for which the term catastrophic is not too strong.

We don’t blame the Afghan government for any of this. This war-torn country, with unrelentingly high levels of violence and poverty, had no experience in negotiating favorable contracts or overseeing complex projects of this nature. They had never done anything remotely like this. We blame the World Bank; for the above reasons, they were given the job of shepherding this project along. They should have ensured that the ore, and the archaeology, were both properly mapped and then compared. They have an entire division dedicated to mining. They should have reviewed, and explained to the Afghans, the various technical options, and the risks.

When we first got involved in 2011, we met a lot of very unhappy archaeologists. The mining company had told the Afghan government in 2010 that they were going to start work in a few months, and that the site would have to be hermetically sealed off because of the explosives they would be employing, and if they wanted any of the relics to be saved, they should bring in salvage archaeologists to remove anything that could be dismantled. After three months, they extended it by another three, then by six … the constant short deadlines had caused the archaeologists to work in artificial haste, not taking time to document much, just piling whatever they could remove into storage facilities. In fact, opening a mine of this type takes four to six years, and all the urgency had been a deception.

We tried to convince the World Bank to hold a meeting of the mining company, the archaeologists, and neutral subject matter experts, to see if maybe there was a win-win solution. When we realized that they weren’t going to do it, we partnered with SAIS Johns Hopkins and convened an Expert Conference in Washington DC. Top-notch professionals from the relevant fields, plus the French archaeologists from Mes Aynak, gave us three days of their time pro bono. Based on their subject matter knowledge, they concluded that first of all there was no rush and NO reason to be conducting rescue archaeology. Second, mining and archaeological work could continue in parallel for the entire lifetime of the mine, given good will and frank coordination. Third, they were highly alarmed by the absence of an environmental impact study and a mine closing plan. Best practices were clearly not being followed here, and the risks were great, in terms of heritage loss and environmental ruin.

ARCH also began to work on legal action: We submitted an amendment to the Afghan mining law. We filed a comprehensive complaint with the Inspection Panel of the World Bank which was financing and overseeing the management of the mining project Eligibility Report and Inspection Panel

We also made sure to provide information to civil society groups internationally and local to Logar Province who undertook activities to protect Mes Aynak. We published in international media outlets.

Ironically, it was the deteriorating security situation in Logar Province – where Mes Aynak is located – that gave this historic treasure a second chance. The mining company folded its tents and departed, and for a few years, all was quiet on the slightly plundered, but mostly still safely buried site.

Last year, in 2018, that slumber ended, and discussions for a revival of the contract commenced. On a positive note, the Afghan government under President Ashraf Ghani seems more attentive to the cultural heritage aspect and the environmental risks. They have told us that the value of this historic treasure is fully clear to them, and that they intend to exercise due diligence to ensure that all technical options are investigated and considered, and that an informed decision is made. They have stated their intention to finally organize that meeting of neutral subject matter experts, and to give them access to whatever information presently exists. That would be really good, we have our fingers crossed and will keep you posted.

The Plan

This is not our first rodeo. The World Bank too, initially promised such a meeting. They called it the “Big Tent” meeting in which civil society, experts and the stakeholders were all going to get together to discuss the way forward. In the end, after multiple postponements, this shrank down to a press conference with only one press outlet attending no discussion, no questions allowed, and no civil society invited. A sympathizer from within the Afghan bureaucracy snuck us in, and we later renamed this disgraceful ploy the “pup tent meeting.”

So as we said, we are optimistic and we are hopeful and we are on course to be of constructive assistance. But if this turns out to be another pup tent, we have our placards ready and our pencils poised to file some legal interventions.

Actions

- In 2012, ARCH published a White Paper on the situation.

- This online petition was signed by more than 84 000 individuals. An earlier version of it was presented to then-president Karzai.

- In the summer of 2012, ARCH partnered with Johns Hopkins University’s Central Asia and Caucasus Institute to convene a technical conference on mining and heritage.

- In the fall of 2012, ARCH submitted a formal request to the World Bank’s Inspection Panel asking for an investigation of this World Bank-overseen mining project. The World Bank’s management team described ARCH as the most effective civil society group active in Afghanistan for heritage protection matters.

- The World Bank adopted several of the recommendations from our conference, and is hosting a follow-up meeting (TBA), based on our model and with our participation

- ARCH lawyers contributed an amendment to the new mining law of Afghanistan

- ARCH provided advisory materials to the former Minister of Mines, Dr. Saba, who expressed his appreciation for the group’s work

- ARCH created the initial Mes Aynak Wikipedia page and produced an educational video educational video in cooperation with TriVison

- Our actions encouraged partners to launch campaigns of their own such as a demonstration in front of the U.N., a documentary film, a signature campaign, and more.

- In August 2018, ARCH learned that the mining contract was once again under negotiation. We contacted the Afghan government and they invited us to express our concerns and suggestions. We mobilized a team of mining professionals who volunteered their expertise, and under their tutelage, prepared the relevant questions to be addressed

- We’ve been invited to take part in a neutral expert meeting, date TBD – let’s see!