The Photo Mario Archive Project: Recapturing the Memory of a Neighborhood Photography Studio

The Photo Mario Archive Project

Recapturing the Memory of a Neighborhood Photography Studio

Mona El Hallak, Lebanon

An interactive installation with photographic prints, archival documents and a video

In September 1994, I discovered the Barakat Building. It was situated exactly on the Green Line that divided Beirut during the 15 years of civil war that I witnessed with my family. In 1924, the building was originally designed for the Barakat family, featuring an avant-garde architectural transparency connecting the residents to the city through its unique central void; but with the outbreak of the civil war in 1975, fire, death and violence left the structure destroyed, abandoned and disconnected from the city. Eventually it became a war machine, as militias and snipers moved in and abused its architectural genius. The overlap between these two histories was amazing, and thus began my fight to preserve this building and turn it into Beit Beirut, or the Museum of Memory of the City of Beirut. I did not imagine then that I would be still working on it 23 years later.

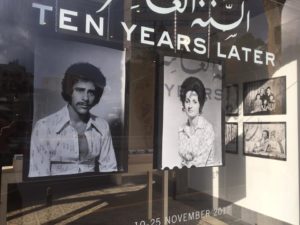

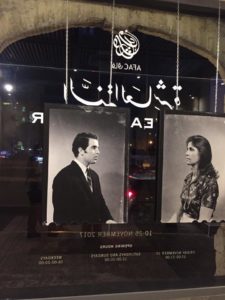

In one of the ground-floor shops, hidden behind the rusted rolling shutters, I found the photographic archive of Photo Mario: around 10,000 bluish negatives of different formats as well as some prints and documents scattered under dust and debris. This archive paid tribute to many bygone studio practices and to the pre-war days when people came to have their photos taken for different reasons and on different occasions. I discovered portraits, passport photos, family photos, baby photos, postcard-like photos commemorating special moments and cherished relationships, all set against different studio backdrops. The first time I held one of the warped negatives against the sunlight and saw a face looking back at me with a pair of white eyes was a transformative moment.

The negatives are time capsules. They represent at once the pre-war era of their timestamp; the time of resilience when the studio was abandoned both during and after the war; the time when they were found, collected, and sorted into an archive; and the time still to come when they have a story, when they are identified by the people who recognize themselves or their family, friends and neighbors. Then, there is the presence of the negatives as objects, almost art installations: they are warped, torn, stained and damaged with the dust they have incurred over the years.

In 1957, the shop was rented out by Samuel and Manuel Ajamian as a photography studio and was abandoned, like the rest of the building, during the war due to its dangerous location on the Green Line. Ephrem, owner of neighboring “Salon pour Dames,” dimly remembers Mario the photographer. Who is Mario and where is he today? Who are all these people looking back at us through these negatives? What stories do they have to tell about the city and the pre-war days? What are their memories of their Photo Mario visit? How can we engage the public in researching this archive, and through their research connect them to the city and its memory?

This project stresses the role of photography as a “technology of memory” that not only documents the past but calls it into the present. My aim is to create an opportunity for people to adopt one or more photos and try to identify the subjects, find them or their families, and collect their memories of the studio, the building and the city. My interest is not only in discovering the stories of the subjects, but in how such stories will be collected by those who choose to be part of this project and in the impact their participation—including their possible failure to uncover the stories—will have on them. I’m interested also in other unrelated stories they might reveal or come across. The Photo Mario Archive Project will become appropriated by the citizens and the stories they bring back will contribute to the permanent collection of Beit Beirut: stories of birth, love, family, friendship, reunion, pride, accomplishment as well as the stories of pain, fragmentation, diaspora, death, survival and resilience that might have followed. The Photo Mario Project will be the story of the many transformations of Beirut and its people during the past 50 years.

Other photos from the Photo Mario Project’s exhibition:

If you would like to contribute to this project, you can visit the exhibition at Beit Beirut, choose a photo and come back with a story to photomarioproject@gmail.com

Learn more about the work of the Neighborhood Initiative at the American University of Beirut, which this project is affiliated with, by clicking on the link.