Report from Prague

May 15, 2016

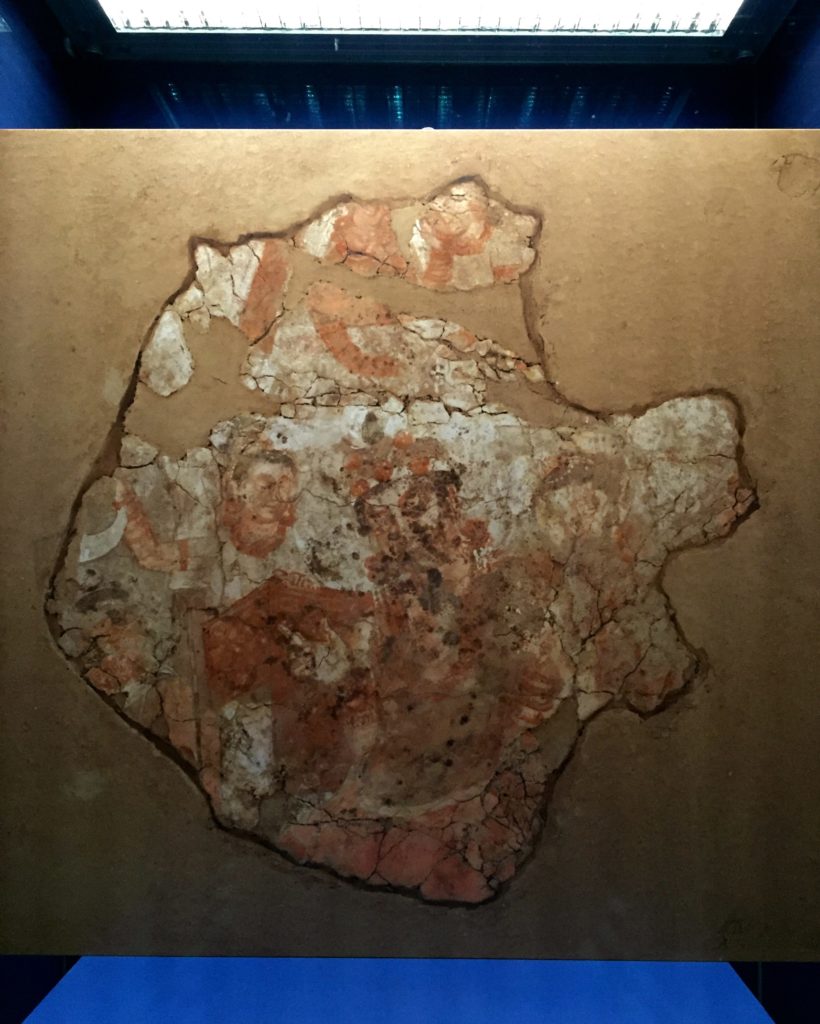

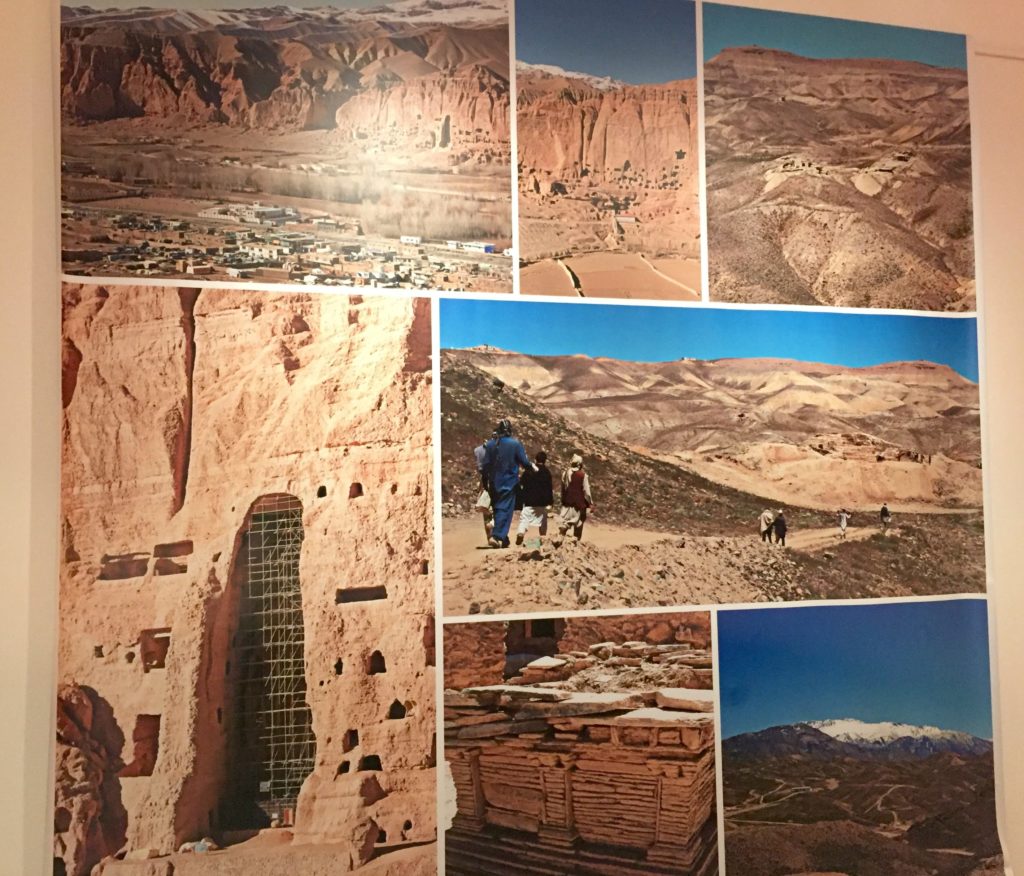

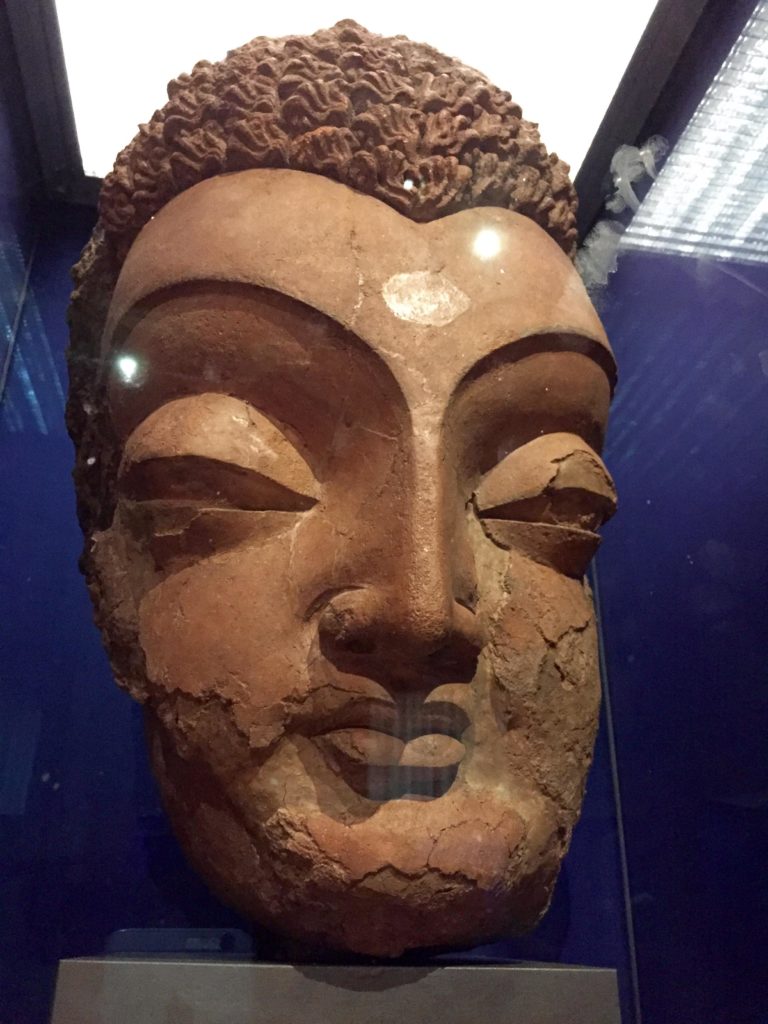

Mes Aynak was a thriving Buddhist city located at one of the crossroads of the Silk Road. Copper was mined here probably from the Neolithic era onwards, and archaeologists expect to find intriguing information about the early history and technology of mining if they are able to excavate the site. In addition to multiple stupas and monasteries, there is a fort that was built to protect the city, its traders and its wealth. There is also believed to be a Zoroastrian shrine. Many stories remain untold, yet to be uncovered.

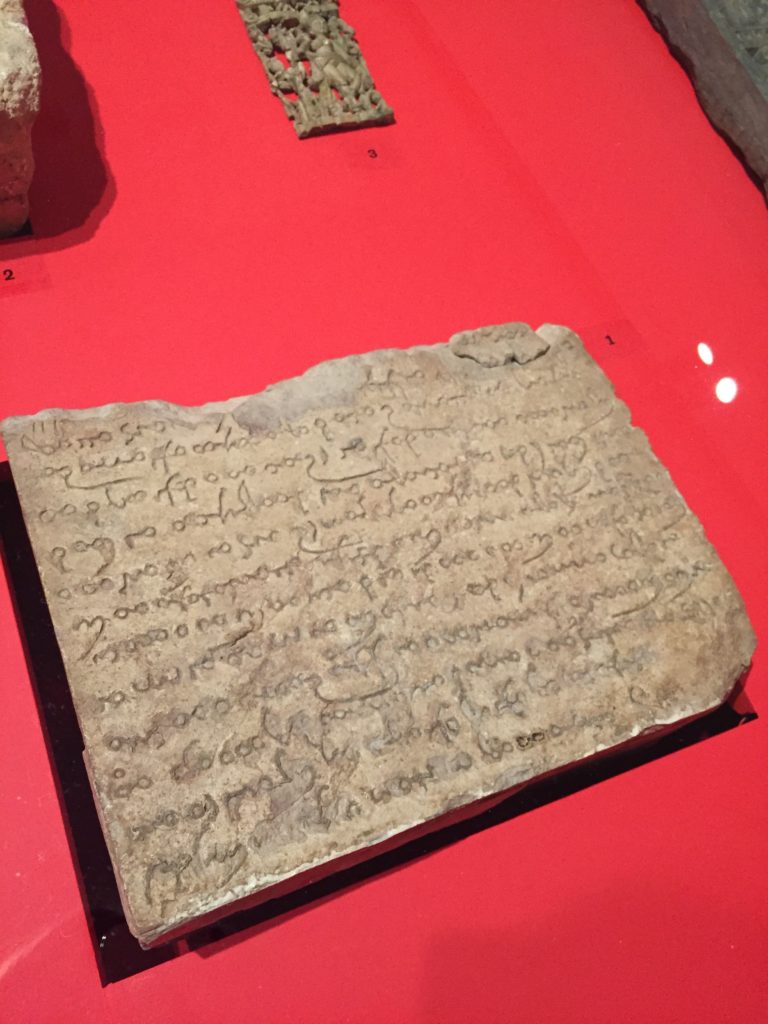

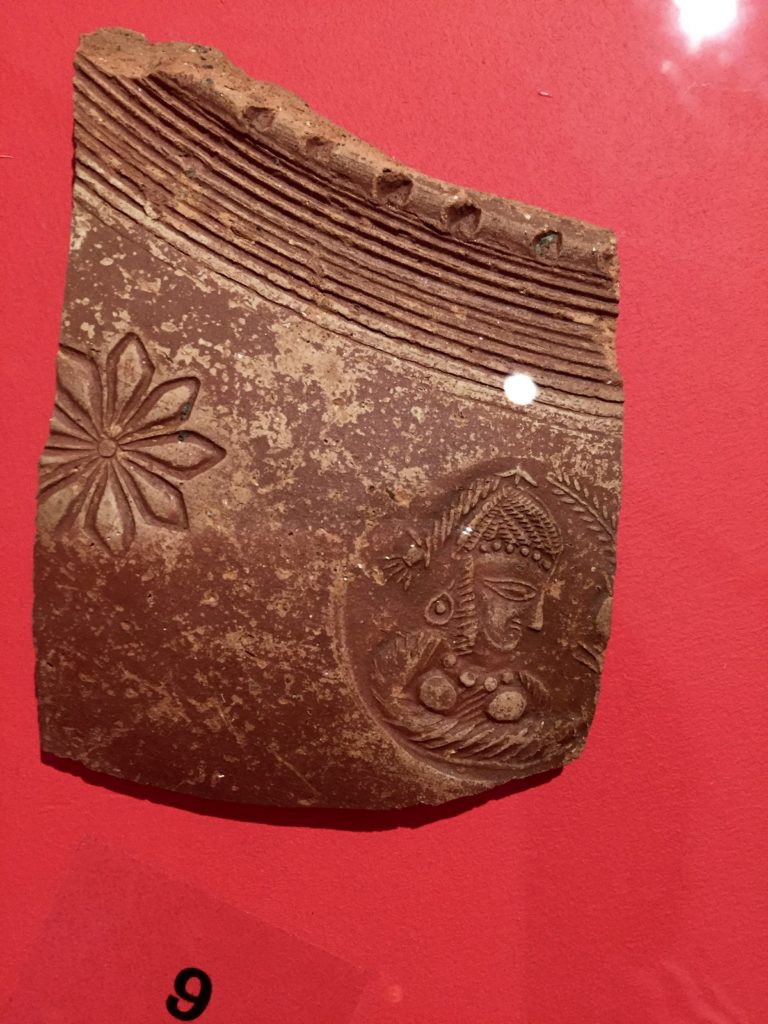

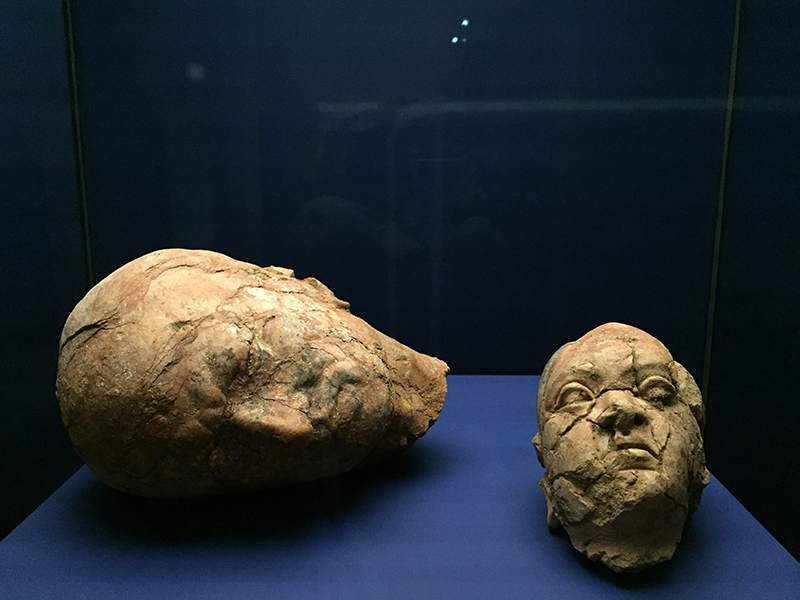

Not only goods were exchanged on the route but also customs, skills, tales, culture and art. For example, artifacts from the Bactrian and Kushan empires show Persian and Greek influences. Image 1 shows three lions and a baby lion. However, as was explained to me, Persian art works usually depict only two lions. This is evidence that this silver bowl from the Kushan period has Sassanian influences while carrying the fingerprint of its own specific art traditions. Furthermore, the curator told me that according to one of his Iranian friends, popular myth holds that the oldest son was not automatically the heir during Sassanian times. Rather, the title would pass to the one who killed a lion.

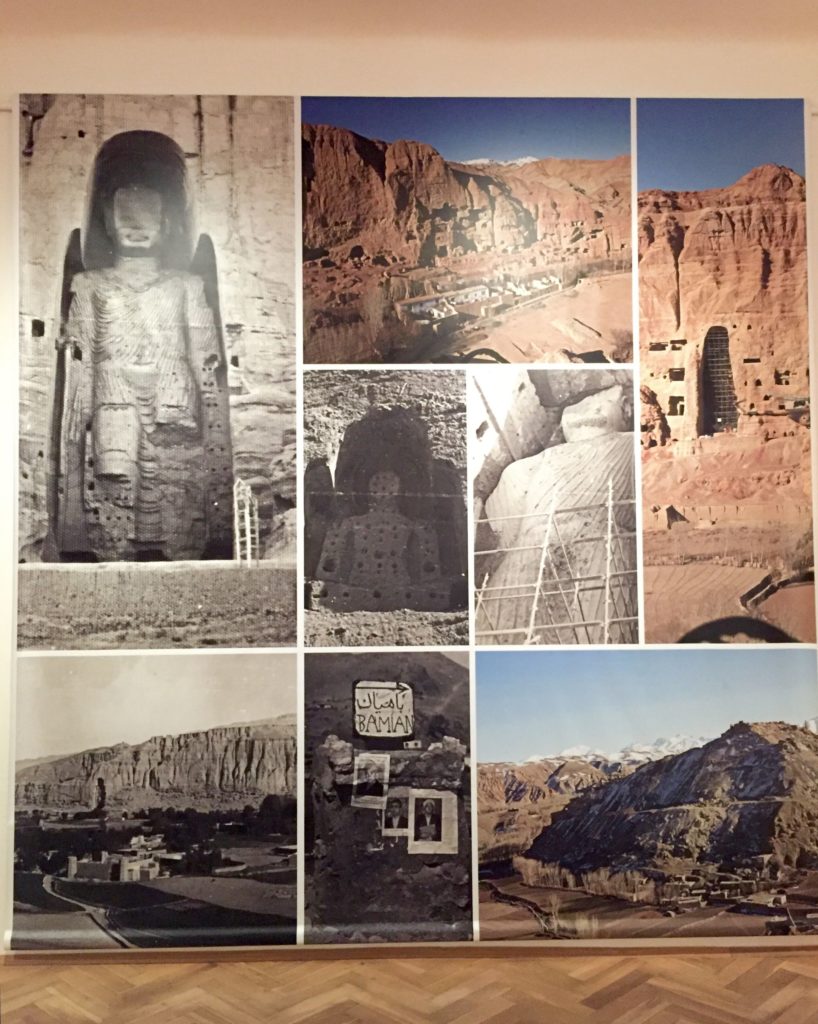

The exhibition in Prague, “Afghanistan – Rescued Treasures of Buddhism,” focuses on the pre-Islamic history of Afghanistan, its Buddhist history in particular. Afghanistan has a rich Buddhist history reaching to the Kushan period, which started approximately in the 1st century AD. “It was through the Kushans that the woolen textiles, gold, and silver of Rome flowed east; the cotton, spices, and semi-precious stones of India migrated north; the silk of China travelled west; and the rubies and lapis lazuli of Bactria and the Tarim Basin moved outwards. The Kushan Empire also played a vital role in the dissemination of Buddhism from India to Central Asia where it eventually found its way to China and then Japan.”

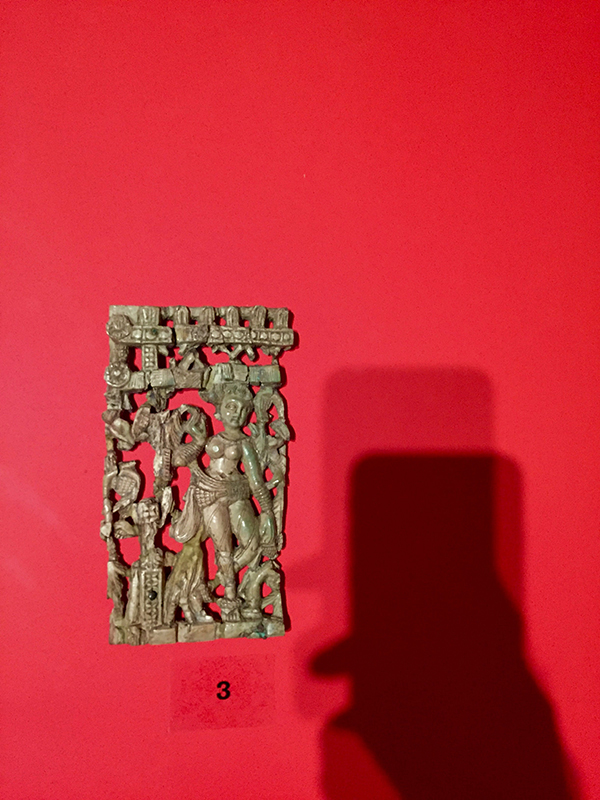

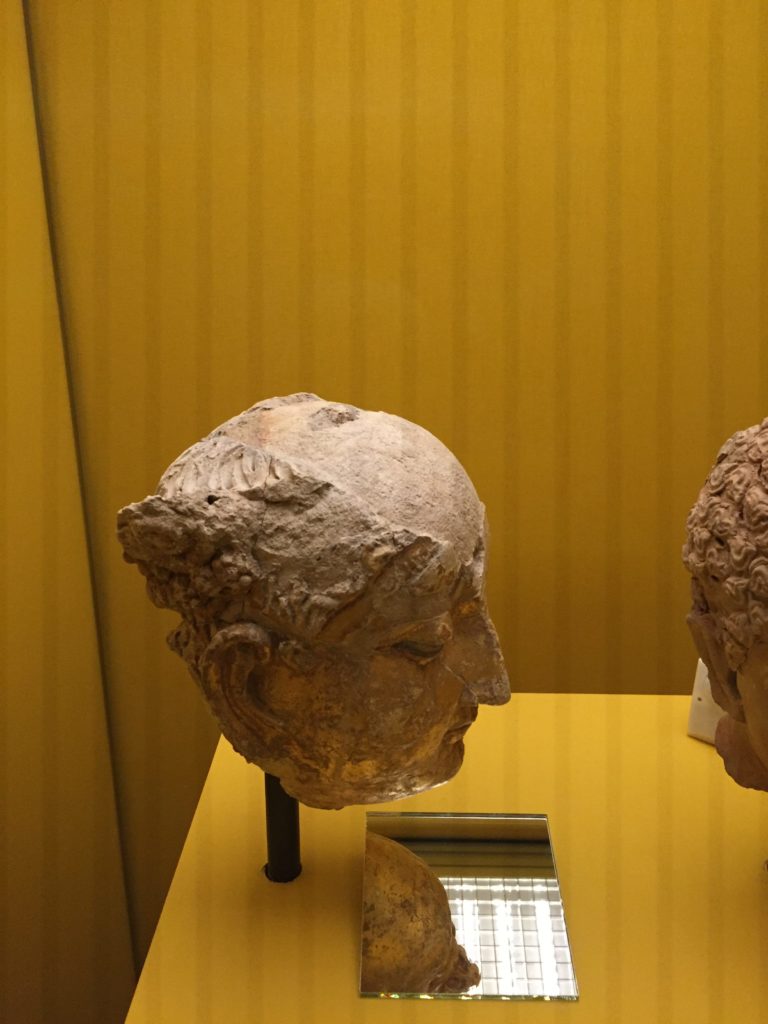

The exhibition is housed in four rooms, and each one – except the second room which is dedicated to a film and to children’s activities – has one of Buddhism’s colors: red, blue, and yellow. Green they left out, I was told, because it is symbolic of Islam. The show’s main curator, L’ubomír Novák, is an approachable, knowledgeable and very friendly man in his mid-thirties, whose diverse interests include Yaghnobi, Vikings, and medieval music. As he explained to me, he got involved in the show by chance. He heard about a project involving Afghanistan so he contacted the director of the museum to offer his assistance, because he is the only one at the Národní Museum (the National Museum) who speaks Persian. To his surprise, he soon found himself assigned to the running of the whole show.

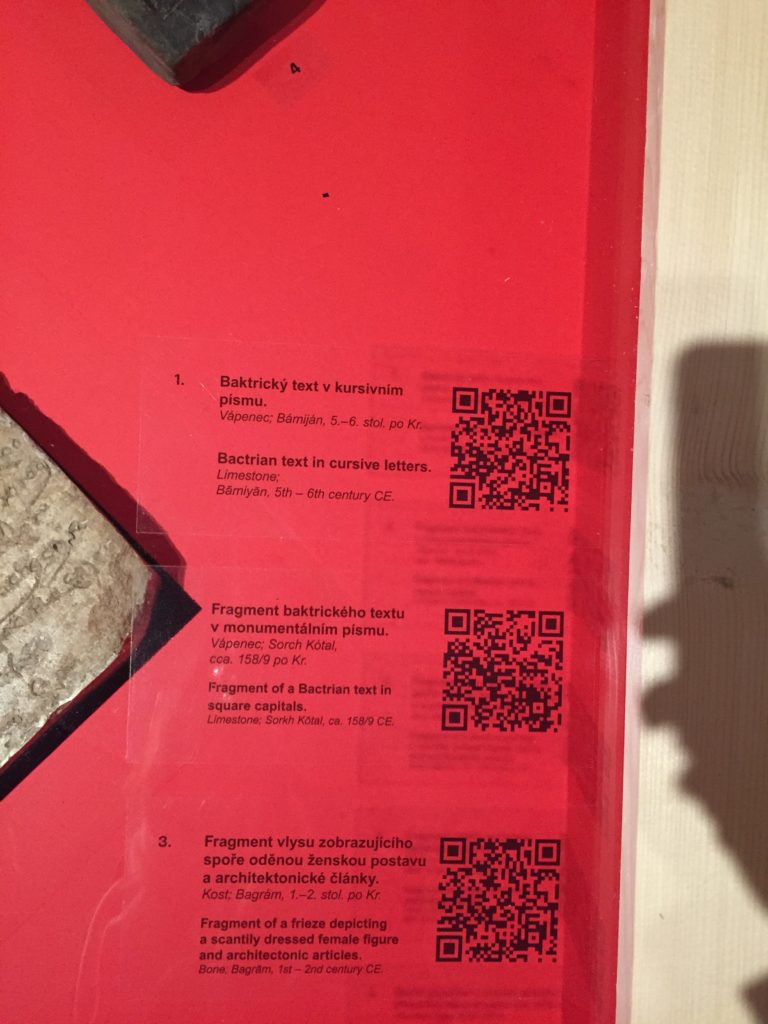

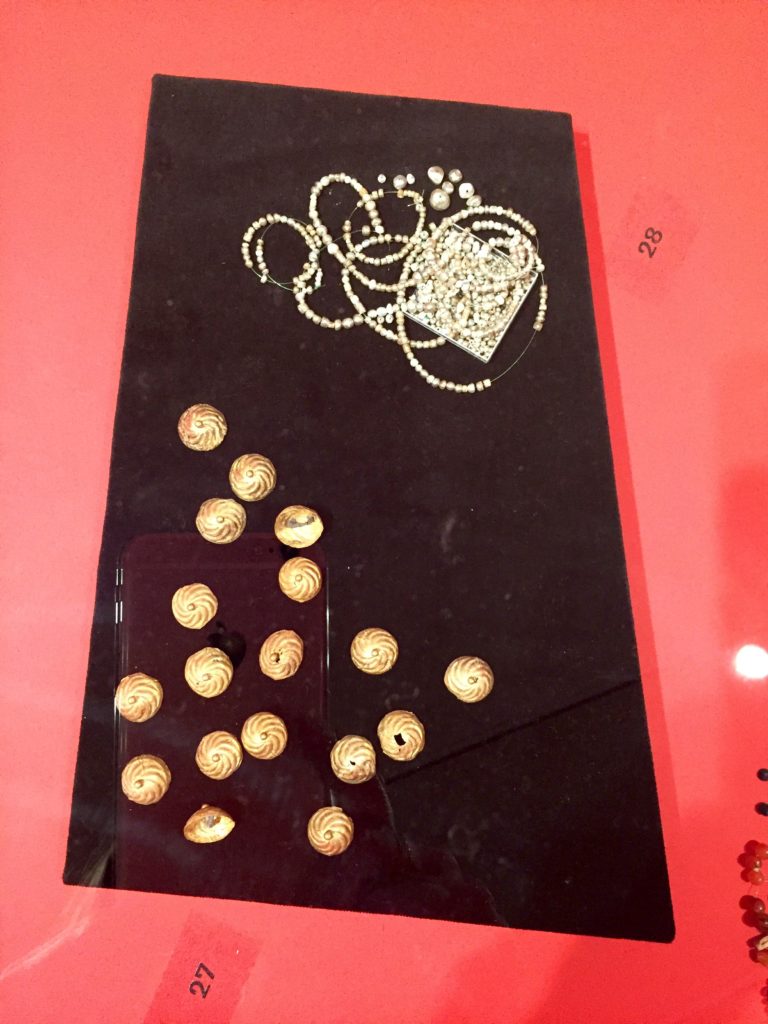

Another, rather unlikely, co-organizer of the exhibition was the Czech military, and the Military History Institute Prague. It is startling to see in the display cases next to a three-winged arrowhead from the 1st to 2nd century CE, a modern item such as a soldier’s Kevlar helmet from 2007-2008 (see image 2) — representing the ISAF mission. Yet upon reflection one realizes that this is sadly appropriate: Afghanistan’s history is defined by wars (Alexander the Great, the Moguls, and the “Great Game” to mention a few). As Mr. Novák pointed out, the first historical reference to the territory of present-day Afghanistan is linked to Persian military campaigns and stems from Darius the Great. As he further explained to me, there is a saying that “all art stops in times of war”, but this does not hold true when it comes to Afghanistan.

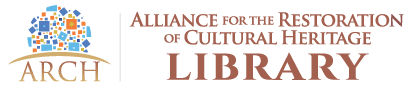

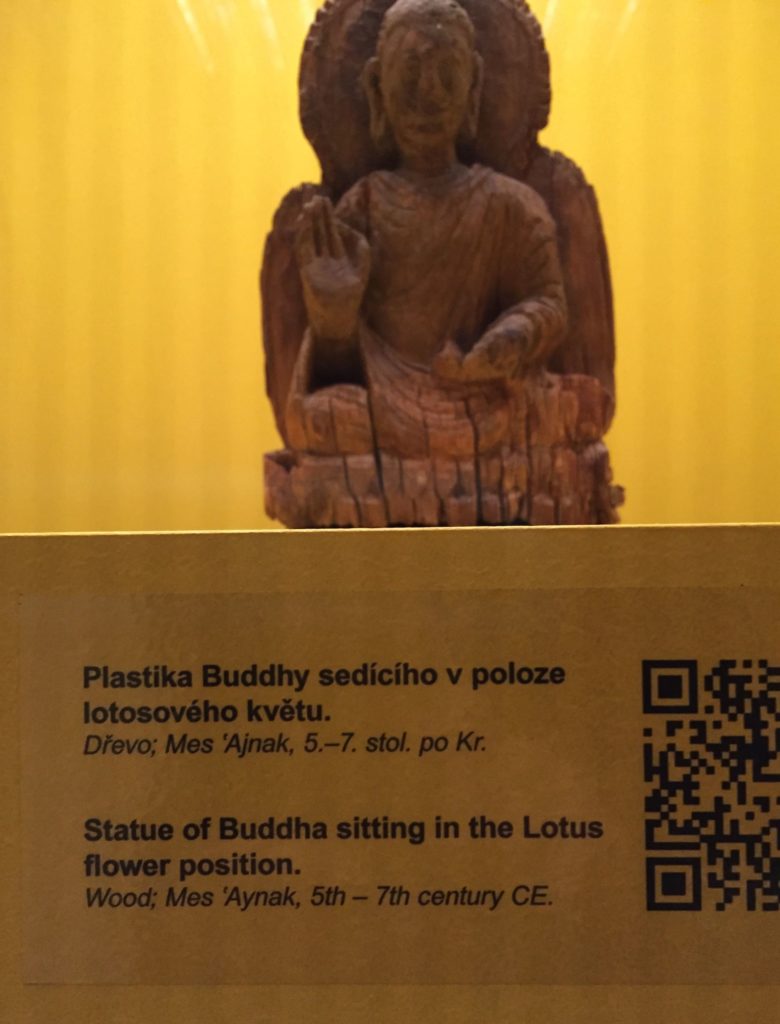

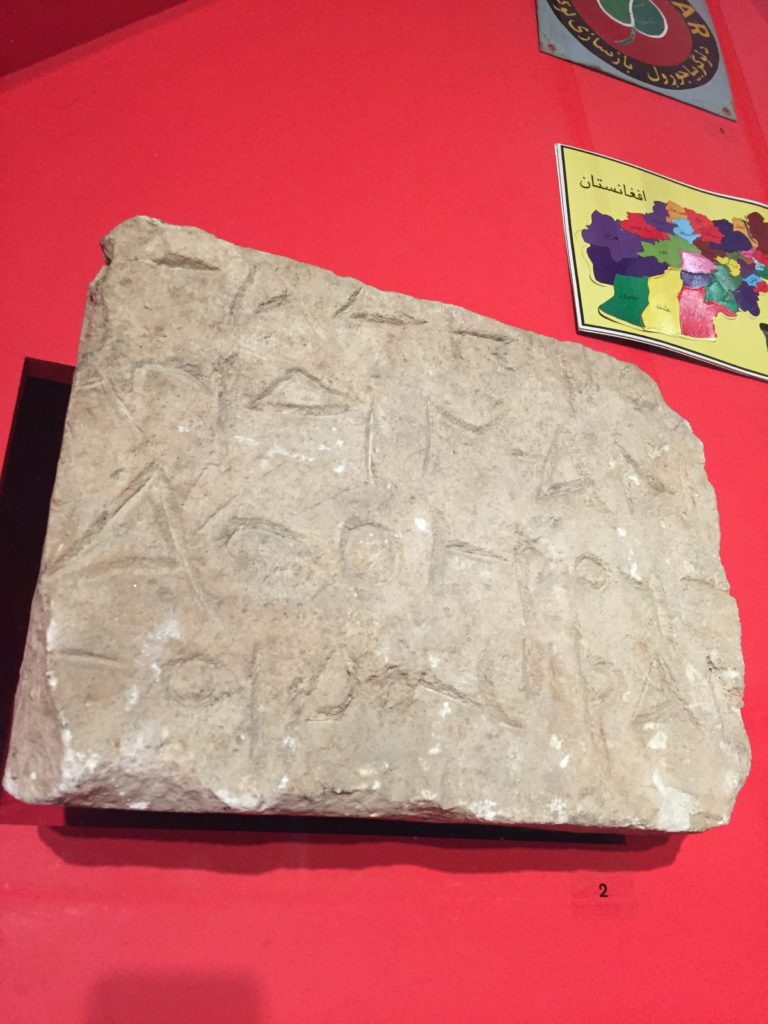

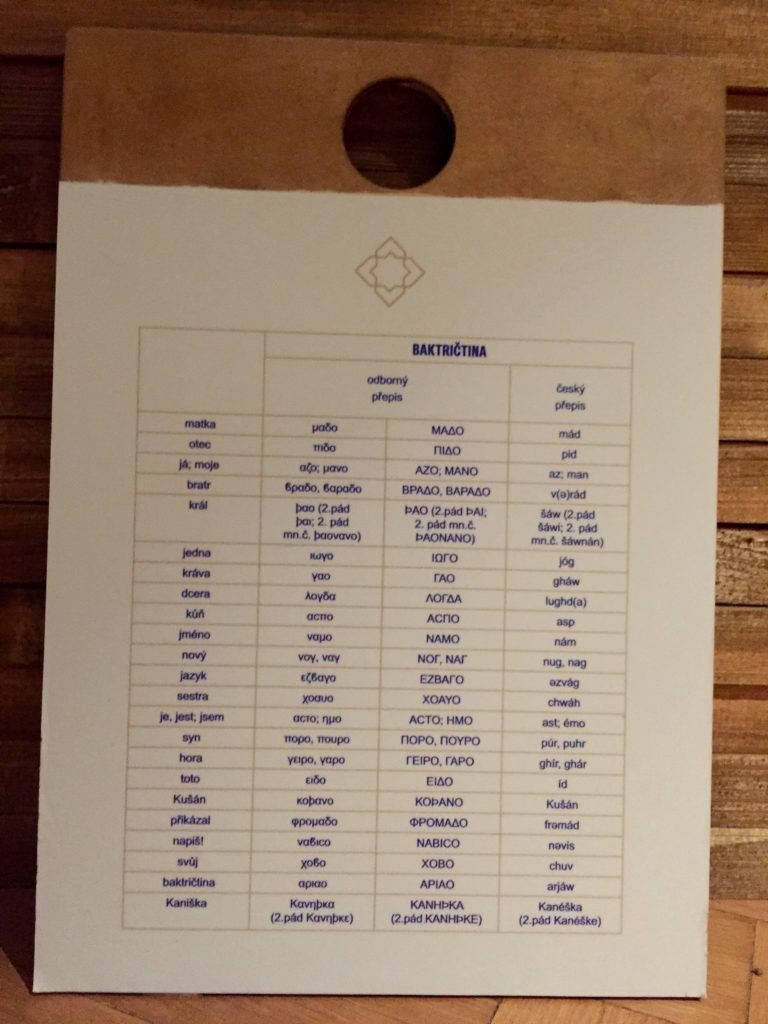

The show is a success of cultural diplomacy and a win-win proposition. In exchange for being permitted to display the artifacts in the Czech Republic, Czech conservators agreed to assist with consolidating the objects. Attached to one showcase (image 3) was a QR code through which the visitor could check the status of conservation of a wall painting, constantly updated to reflect progress. This feature allowed for step-by-step observations of how the mural looked in its worst state and how it is being restored. The Czech side fulfilled its obligations and the archeological findings are currently being wrapped and packed up to be shipped back to Afghanistan.

As an organization that has been involved in campaigning for the Mes Aynak since 2012, we at ARCH were very excited to experience the display of these treasures and are inspired to continue in our efforts to save Mes Aynak as a real place and a real city for people in the future to visit – not just in the form of a few statues and artifacts ripped from their place and deposited in a museum.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]